Ontario Premier Doug Ford has just revealed the first fiscal roadmap and it might just be a renters' worst nightmare. Starting November 15, 2018, rent control rules will no longer apply to buildings and units being rented for the first time.

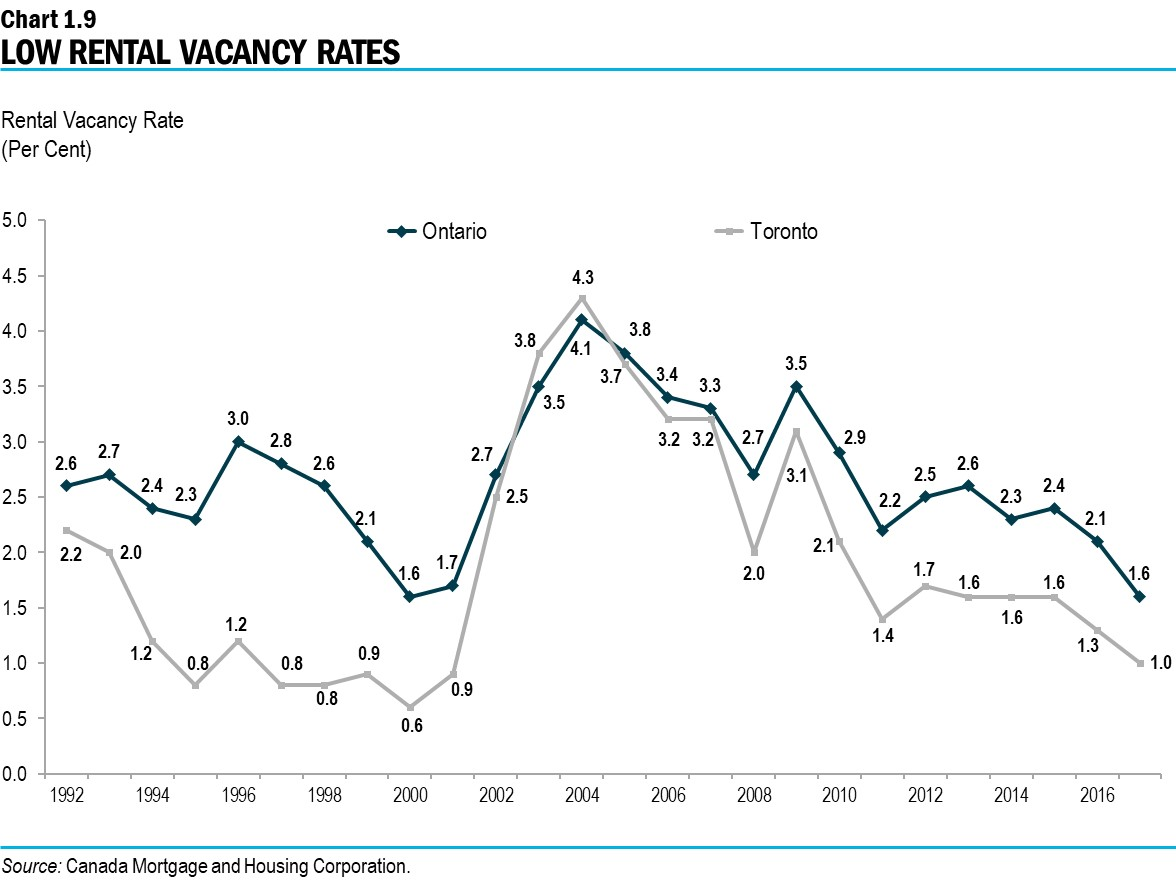

The plan to remove rent control for new buildings is meant to address the undersupply of purpose-built rental units, which has contributed to historically low vacancy rates in the rental market. The limited supply growth can be traced back to Rent Control policies that have weakened investment incentives and construction activity. To address these challenges, the government has taken the step of enacting policies to increase the supply of housing across Ontario.

Geordie Dent, executive director of the Federation of Metro Tenants’ Associations, called it a return to the “economic evictions” of former PC premier Mike Harris.

Part of this initiative is the reintroduction of the rent control exemption, which will apply to new rental units occupied for the first time after November 15, 2018. The idea is that this will help create market-based incentives for supply growth, encouraging an increase in housing supply in order to meet the housing demand of Ontario residents.

The line chart above shows the rental vacancy rates in Ontario and Toronto between 1992 and 2017. The vacancy rate had been in decline between 2004 and 2017. The current initiative aims to tackle this declining vacancy rate.

Previously, all properties were rent controlled and governed under the Residential Tenancy Act (RTA). The RTA states that a landlord cannot increase rent by more than the percentage provided by the Rent Increase Guideline, which is calculated by the Ontario Consumer Price Index (a maximum of 2.5%). As of recent, this limitation will only apply to older units which were occupied prior to November 15, 2018.

What implications does the new rent control in Ontario have?

What does this mean for renters? It means that if you were to move into a brand new unit (i.e were the first tenant to occupy it), then your landlord could increase the rental price each year as they please.

What does this mean for housing supply? Well, the theory is that the lack of rent control will incentivize developers to start more purpose-built rental developments, which in the long run will increase the supply of rental units in Ontario. This is especially true for the city of Toronto. As a result, rent prices would gradually plateau.

In general, economists shudder at the thought of rent control. The Swedish economist Assar Lindbeck once called it "the most efficient technique presently known to destroy a city—except for bombing." But, with rent levels in cities like New York making life increasingly unaffordable for many residents, lawmakers see rent control as a fix they can deliver immediately.

Yet, study after study has shown that over the long term, rent control only contributes to the problem. They've found that rent control reduces the quality and number of rentals on the market. Putting a cap on housing prices, most economists argue, makes building and improving a home less attractive. The government, by artificially lowering the return on renting, decreases the incentive of developers and landlords to get into the renting business, which means fewer and lower quality rentals.

Economists believe skyrocketing rents are the free market's way of saying, "Hey, I'm sorry—but I can't fit you all here. We're going to need more houses." By discouraging supply, rent control adds to this problem rather than solving it. But giving up and leaving it to the market may or may not solve the problem. It's certainly more boring, so here are other ways to solve the housing mess:

- Social Insurance. Bloomberg opinion columnist Noah Smith likes the idea of "a citywide system of government social insurance for renters. Households that see their rents go up could be eligible for tax credits or welfare payments to offset rent hikes, and vouchers to help pay the cost of moving. The money for the system would come from taxes on landlords, which would effectively spread the cost among all renters and landowners instead of laying the burden on the vulnerable few." (Read more here).

- Better Transportation Options. The Bipartisan Policy Center stresses transportation is key to expanding housing options for people. Better transportation makes commuting easier from areas with more affordable rental options. (Read more here).

- Build New Homes On Existing Roofs. The British property consultancy Knight Frank did a geospatial analysis of central London and found that as many as 41,000 new homes could be built on top of existing roofs. If you can't expand outward, expand upward! (Read more here).

- Non-Profit Organizations For Affordable Housing. According to MIT economist Albert Saiz, in the Netherlands, "75 percent of that nation's 3 million rental units are provided by nonprofit housing associations. These associations purchase and develop apartments for rent. They compete with investors in the open real estate market." Maybe we could do more of that in Toronto. In addition, advocacy groups such as Rent ON are advocating for an approach geared towards developing purpose-built rental units (Read more here).

It looks like this new initiative is double sided. It can incentivize landlords to get rid of under paying tenants and promote developers to build more homes in Ontario, that might just make housing more affordable in the long run. Let's hope it's the latter.

For a deeper dive, check out the Toronto Star's take on the legislation and the perspective of the tenant and housing experts they interviewed who state that removing rent control on new units won’t ease acute Toronto’s housing crisis.